The World Turned Upside Down: Revolutions in the Microcosm and Macrocosm, and the Crystalline Humor in the Three Eyes of Early Modern Optical Anatomy. Part Two.

The World Turned Upside Down: Revolutions in the Microcosm and Macrocosm and the Crystalline Humor in the Three Eyes of Early Modern Optical Anatomy

Part II. The Revolution of the Eye and De-centering the Eye’s Sovereign

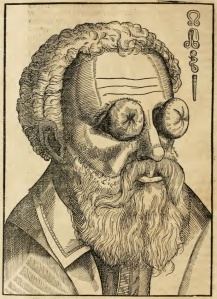

In the first section, I discussed Andre du Laurens’ extended metaphorical treatment of the eye’s structure. There, du Laurens represents the crystalline humor as the “sovereign” of the domain of the eye and as a Herculean figure heroically standing between the external and internal lights. Du Laurens’ metaphorical elaborations reflect and illuminate the importance with which theorists of vision and optical anatomists already attributed to the eye and its structure. The metaphors highlight the emphasis elsewhere on the organization of the eye and the early modern tendency to see correspondences and hierarchies within the structure of nature and the human body. Such popular discourses additionally shaped the understanding of the eye in elite discourses, locking the two in interpenetrating chains of influence.

In the elaborate chains of correspondences slowly eroding yet still powerfully influential in the early modern period, similarities in structure, resemblance, and appearance or in relationships or connections bespoke real rather than simply metaphorical chains of signification. In bestiaries, the appearance or form of an animal bespoke some of its hidden vertues. In herbals, a plant resembling a sexual organ could possess the real power to affect the sexual organs. In a psychophysiological model, the “black bile” of melancholy was or caused “black” thoughts and, in some, delusions of dark shapes. In anatomy, the circular and square figures found in the human form represented the most perfect shapes within the created world. In optical anatomy, the eye’s shape and structure resembled and reflected the structure and order of the cosmos.

Du Laurens sees the image of political authority in the eyes’ structure, and, in this section, I will turn to the eye’s resemblance to the cosmos. As the corporeal world and its light were proper objects in the eyes, its shape, order, and structure and its similarity to the shape, order, and structure of the world carried with it a powerful set of correspondences that shaped the sense of sense.

It is interesting that the revolutions in both theories of the microcosmic eye and theories of the macrocosm occur at roughly the same time and through the influence of Johannes Kepler. Following his contribution to the science of each, there would be revolutions in each that de-centered the central component within both systems. Kepler is probably best known for his contribution to the radical revolution in early modern science that, when elaborated and built upon, overturned the Ptolemaic conception of cosmography. Kepler challenged the Ptolemaic model and defended and elaborated upon the work of Nicholaus Copernicus of nearly a century before. The eventual adoption of the Copernican system with the earth no longer situated at the center of the cosmos de-centered the Earth and its inhabitants within the frame of the universe.

Less discussed, however, is the revolution Kepler accomplishes in his optical anatomy, which, I argue, remains linked to, and might prove more important than, his role in creating a revolution of the heavens. Discussed lesser still are the changes occurring from roughly 1543 to 1619 of optical anatomy itself. Kepler plays a role in revolutions in both the macrocosm and the microcosm. These dual revolutions and their relationship with the elaborate systems of correspondences in pre-scientific eras that linked microcosm to macrocosm, give me occasion to return to the structure of the Galenic eye and the mediate early modern eye.

The spherical shape of the eye and the placement or near placement of the crystalline humor in its center makes the eye a prime candidate for analogical relationships between the microcosm of the eye and the macrocosm. Such a correspondence did not escape the notice of Helkiah Crooke, who, although he challenges vision’s position as the superior sense, draws on Galen to describe the beautiful structure of the eye, explaining that the primacy of vision might depend, in part, on its shape as well as upon its being a microcosm. Crooke says,

[Galen,] being a man of great and profound knowledge, … considered that the Eye was the true Microcosme or Little world in respect of their exact roundnesse and revolutions: wherein besides the Membranes which I dare boldly call the seaven Spheres of Heaven, there be also the foure Elements found. (Crooke [652][i]).

The “exact roundnesse and revolutions” of the eyes commend them not only as reflections of the macrocosm’s perfection, but also, by virtue of that correspondence, speak to the “excellencie” and nobility of the sense of sight. Crooke notes in an earlier section devoted to the “admirable proportion of [man’s] parts” and the human body as a microcosm that

in this proportion of his parts, you shall finde both a circular figure, which is of all other the most perfect; and also the square, which in the rest of the creatures you shall not observe. (Crooke 6).

In this description of Virtuvian man, Crooke notes that the circle and sphere are “the most perfect” shapes. In many descriptions of the Galenic eye, the perfectly spherical eye and the perfectly centered and spherical crystalline humor bespeak the eye’s importance and grandeur. In emphasizing the human eye’s perfectly spherical shape, Crooke follows both the Galenic eye and the mediate early modern eye’s emphasis on the perfectly orbicular shape. Jest as the heavens in a geocentric Ptolemaic system consisted in concentric perfect spheres, the structure of the eye follows that postulated heavenly structure.

In the passage quoted above, one catches another reflection of the macrocosm in the microcosm of the eye. Crooke mentions two more aspects of optical anatomy which argue that the eye is a microcosm within the body. First, he mentions that seven “Membranes” or coats resemble and reflect the “seven Spheres of Heaven,” and, second, that the eye contains “foure Elements.” In the first, the microcosm of the eye includes seven concentric spheres which resemble the Ptolemaic macrocosm. While Crooke does not go on to make such an explicit connection, taking his description one step further, places the crystalline humor in a position that corresponds to the Earth in this Ptolemaic structure of the microcosm, placed at its very center.[ii]

The crystalline humor or lens, when mapped onto this model, occupies the position of the Earth. Such an analogy reveals an interesting aspect of the eyes’ organization in Galenic, and even in the mediate, early modern eyes. The crystalline humor, thought to receive “impressions” or “actualize” the species of external objects, in effect, recreates the visual world within its substance.[iii] The eye not only stands at the center of the microcosm of the eye like the Earth, but also recreates or manufactures simulacra of the world and its objects. I will return to develop the paramaterial aspects of Crooke’s and others’ discussion of the “matter” acquired by the external senses in more detail in a later post.

Second, the microcosmic eye, according to Crooke, contains the four elements of the macrocosm. Crooke rhetorically asks after declaring that there is “Fire” in the eye, that

there is Aire who will denie which understands with what plenty of spirits they do abound? As for Water, who doth not see it in the Eye doth prove himself more blind then a beetle, all the other parts we will liken to the Earth. (Crooke [652]).

According to Crooke, the eye not only reflects the cosmos in its shape and structure, but also in its elemental constitution. Such a description further links the world of the eye to the universe as a whole, analogically confirming that both the eye and the cosmos reflect the majesty of a divine creator. As such, even though Crooke elsewhere shows evidence of post-Colombo ocular anatomy, where the crystalline humor did not occupy the exact center of the eye, and, although he declares touch rather than sight the predominant sense, Crooke still solidifies the eye’s representation as a smaller microcosm nestled within the larger microcosm of the body analogically connected to the macrocosm.

The corporeal eye, with the corporeal world, its objects, and its corporeal light as its objects, conforms to the nature and structure of that world. While I will not go into Crooke’s discussion of the visible species in this essay, I will say that his description also reflects how the eye received or “actualized” mimetic quasi-material, or, as I call them, paramaterial objects that recreated the visible world within the orb of the eye. Even if one does not accept my characterization of the visible and sensible species as paramaterial, the eye still not only reflects the nature of the visible world but also creates mimetic copies of the world upon which it looked.

Such relationships and associations extend beyond the discourses of anatomy and science. Drawing on the same analogical links, university wit Thomas Tomkis gives a similar speech to his character Visus, or vision, in Lingua or Combat of the Tongue and the Five Senses for Superiority.[iv] In Tomkis’ play from the early seventeenth century, the tongue demands to be included as an addition to the five external senses, and disrupts the traditional hierarchy of the external senses by trying to convince the ruler Common Sense that she should not only be considered as a sense but also should sit atop the hierarchy. When called before Common Sense and Phantastes to explain his superiority over the other senses, Visus includes, among other things, his stately residences and their situations in the head, saying,

Under the fore-head of mount Cephalon,

That over-peeres the coast of Microcosme,

All in the shaddowe of two pleasant groves,

Stand my two mansion houses, both as round

As the cleare heavens, both twins as like each other:

As starre to starre, which the vulger sort,

For their resplendent composition,

Are named the bright eyes of mount Cephalon:

With oure faire roomes those lodgings are contrived,

Foure goodly roomes in forme most sphericall,

Closing each other like the heavenly orbes. (Tomkis G2 verso).

In Tomkis’ nesting metaphors, the eyes become a stately “round” manor containing four “goodly roomes” whose perfect sphericality reflect the perfect spheres of the heavens. While Tomkis’ Visus mentions only four rooms rather than seven and while he frames it through the metaphor of the house, he still asserts the structural relationship and analogical links between the eyes and the heavenly spheres.

As with Crooke’s later discussion of the eye’s structure, Tomkis’ Visus offers the eyes’ shape and structural resemblance to the macrocosm as testimony for his supremacy within a hierarchy of the senses. Again, like Crooke, Tomkis might be challenging the conventional understanding of the superiority of sight, but both still continue to underscore how important seeing the eye as a microcosm was during the period.

Again, we find the crystalline humor occupying the central position and represented as the seat of visual power. While Tomkis’ play situates the visual power in subjection to the powers of the internal senses, he also represents the crystalline humor as Visus’ seat, saying that the fourth and most central room is

… smallest, but passeth all the former,

In worth of matter built most sumptuously:

With walls transparent of pure Christaline.

This the soules mirrour and the bodies guide,

Loves Cabinet[,] bright beacons of the Realme,

Casements of light quiver of Cupids shafts:

Wherein I sit and immediatly receive,

The species of things corporeall,

Keeping continuall watch and centinell. (Tomkis G2 verso).

Central to the manor of the eye is the room of “pure Christaline” where Visus “sit[s] and immediatly receive[s]/ The species of things corporeall,” and here we possibly see again, as late as 1607, the model of the Galenic eye. While Tomkis might have been aware of Colombo’s corrections to this arrangement, he does not say so here. As I discussed in part one of this essay, even in texts that represent the mediate early modern eye, including Crooke’s own later Microcosmographia, the verbal descriptions of the mediate early modern eye and the Galenic eye were often spoken of in similar terms. This shows, I think, the power of the analogical relationships and significance of the systems of correspondences that deployed the concept of the microcosm to the figure of the eye, especially when it comes to popular culture even if Tomkis understands the eye as structured like the mediate early modern eye.

Tomkis’ play also dramatizes the connection to the internal senses and its reception of the species in what I am calling the paramaterial mind. While I can provide only a brief sketch here, I will be exploring the paramaterial sensory system more in future posts and provide lengthier sketches in my previous posts. Tomkis represents Visus as subservient to Common Sense, the ultimate seat of judging immediate perception and assembling the discrete species received by the external senses. It was also this system of the paramaterial that the retinal image would help eventually dismantle.

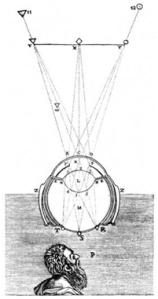

The optical revolution of Felix Platter and Johannes Kepler had already started by the time Thomas Tomkis wrote his play in 1607 and Helkiah Crooke first published his Microcosmographia in 1615. In 1583, Platter argued that the optic nerve was the seat of vision, and, in 1604, Kepler further developed some of Platter’s, achieving a broader acceptance of the retina and the retinal image as the most significant part of the eye. More work needs to be done to map out the lines of transmission of Kepler’s work on optics as it spread and affected optical anatomy, but what is certain is that Kepler’s theory ultimately contributed to a type of conceptual regicide of what André du Laurens previously declared the eye’s “sovereign,” the crystalline humor, and may have had consequences for the system of correspondences that seemed to require the microcosm of the eye’s conformity with and relationship to the macrocosm.

Platter likened the crystalline humor to a looking-glass that projected light upon the retinal screen, describing,

Primario, crystallinus humor, perspicillum est nervi visorii: at qante ipsum & pupilae formen collactus, species oculo illabentes veluti radios colligit, & in ambitum totius retiformis nervi diffundens, res majores ille, ut commodius eas perciperet, perspicilli penit nodo, representat. (Platter 187).

[Primarily the crystalline humor is the perspicillum (*looking glass) for the optic nerve, but as to the crystalline humor and the pupil, the visible species enters as a collection of rays, and diffuses itself on the whole of the retinal nerve, representing bigger things than the small glass represents.]

But Platter never elaborated upon or demonstrated the concept convincingly, and did not, publically and in print anyways, acknowledge that the retinal image would be inverted with respect to horizontal orientation and flipped with respect to the vertical.

This later development and acknowledgement would come with Kepler, who declares:

Visio igitur fit per picturam rei visibilis ad albam retinae & cauum parietem; & quae foris dextra sunt, ad sinistrum parietis larus, sinistra ad dextrum, supera ad inferum, infera ad superum depinguntur: viridia etiam colore viridi, & in universum res quaecunque suo colore intra pingitur; adeo ut, si possibile esset picturam illam in retina foras in lucem protracta permanere, remotis anterioribus, que illam efforma bant, hominiq; alicui sufficiens esset visus acies, is agniturus esset ipsissiman hemisphaerii figuram in tam angusto retine complexu. (Kepler 170).

[The vision then becomes a visible pictura on the white and curved retinal wall, and things which are outside on the right, are depicted on the left wall; left to right, upper to lower, lower to upper. Green colors appear green, and the whole thing, whatsoever its color, is depicted upon the retina, so that, if it were possible for a man to maintain the system’s light on the retina when removing the back of the eye, he would see a figure of the whole hemisphere remains in that small space of the retina.]

Unlike Platter, who described the crystalline humor as the “looking-glass” for the retina and placed the seat of judgment in the optic nerve but did not mention the retinal inversion, Kepler confronts this theory directly and publically in print after developing the theory of the retinal image more extensively than his predecessor. Displacing the crystalline humor itself was an intellectual insurrection, as was the previous trend in early modern optical anatomy that de-centered it within the eye, but acknowledging the retinal inversion began the revolution within the eye in earnest. Both moves, however, challenged not only prior medical authorities that considered the crystalline humor the eye’s sovereign, but also the cultural beliefs surrounding and shaping the sense of the eye and its structure.

Acknowledging that the eye did not see in the same way that either the visual plane laid out before the eye or as it was perceived in the mind that Kepler’s theory is profoundly revolutionary. Not only did such theories allow the retinal screen to usurp the position of primacy previously held by the crystalline humor, but they also turned the eye’s image upside down within the eye itself. The image within the eye, for the first time in recorded human history, was recognized as upside down. From the perspective of an early modern, the world (at least within the eye) no longer looked as it appeared. Revolutionary in both senses, Kepler challenged a fundamental way in which observers perceived and engaged with the world as a whole. I do not mean to suggest that Kepler’s singular genius emerged out of a historical vacuum, but I do want to suggest that the development of the very ability to recognize the inverted retinal image itself and its subsequent effects constituted a real radical shift and break with traditions of the past towards something new and modern even if it took some time for culture to recognize and realize those revolutionary consequences.

The retinal image, itself revolutionary in its movement towards a modern understanding of vision, also had other revolutionary consequences that would only reveal their full effects once the quasi-Aristotelian system of the paramaterial sensory system and mind were altered and abandoned. Whereas previously the crystalline humor received the visible species of corporeal things, transmitting them through the “spirits” to the inner senses and the brain, the retinal wall would eventually become an opaque wall that blocked the paramaterial transmission of these species. The species survived the retinal image and inversion, but, I argue, also challenged some of the conventional popular associations and its traditional theorization. The sensible species and especially the intellectual species persisted in some form until they disappeared into something like the Lockean Idea.

Kepler himself famously chose not to follow the visual image, species, or, as he calls it, pictura as it entered the human brain and mind, saying,

Visionem fieri dico, cum totius hemisphaerii mundani, quod est ante oculum, & amplius paulo, idolum statuitur ad album subrufum retinae cauae superficiei parietam. Quomodo idolum seu pictura haec spiritibus visoriis, qui resident in retina & in neruo, conjungatur, & utrum per spiritus intro in cerebri cauernas, ad animae seu facultatis visoriae tribunal sistatur,an facultas visoria, ceu quaestor ab Anima datus, e cerebri praetorio foras in ipsum neruum visorium & retinam, ceu as inferiora subsellia descendens, idolo huic procededat obuiam, hoc inquam Physicis relinquo disputandum. Nam Opticorum armatura non procedit longius, quam ad hunc usq; opacum parientem, qui primus quidem in oculo occurrit. (Kepler 168).

[I say vision is accomplished, when the whole hemisphere of the world which is before the eye, and bit more, an idolum stands on the curved, reddish-white retinal wall. How the idolum or pictura joins the visual spirits, which reside in the retina and the optic nerve, and whether it is made to appear before the soul and the tribunal of the visual faculty by the spirits in the brain’s caverns, or whether the visual faculty, like a magistrate sent by the soul, descends to the lower court to meet the idolum, I leave to the dispute of physicists. For the opticians’ troops do not advance beyond this first opaque wall met with in the eye.]

Kepler refuses to proceed past the retinal screen, halting his inquiry once he follows the path of light through the lens and onto the rear surface of the eye. Not only does Kepler offer the first explication of the real image formed on the retinal screen, but he also interposes an “opaque wall” between the eye and a perceiver in a way not previously in place in earlier theories of the crystalline humor. Whereas before the images received or formed by the crystalline humor found their way into the inner senses through mediating spirits through to the gatekeeper of the sensus communis, the pictura here seems stuck on the rear wall of the eye.

This additional barrier that strengthens the boundary between the eye and the mind started with Vesalius’ observation that the optic nerve was not hollow. While Kepler gives a nod to the quasi-Aristotelian model of perception in the second half of this passage, it is my contention that the interposed retinal wall further fractured earlier popular theories of sensation and perception. Additionally, I think this wall between the eye and the mind takes part in a general and much broader transition from a paramaterial mind and “selfe” to more of a perimaterial sense of the modern self. In brief, I mean the transition from a less bounded and insular “selfe” towards a less permeable and porous modern self.

As I discussed earlier in my sections on Crooke and Tomkis, even with the revolutionary potential of Kepler’s retinal inversion, the change to popular understandings of vision emerged very slowly, and it was not until Scheiner in 1619 that a representation of the modern eye appeared in print. Just as the Galenic eye might have popularly survived Colombo’s corrective to Vesalius’ optical anatomy, the belief in the centrality of the crystalline humor survived, at least for some time, beyond Kepler. While creating more public controversy, the transition from a Ptolemaic universe to a Copernican one also took some time. While the revolutions in the microcosm and the macrocosm had begun by the first quarter of the sixteenth century, they were far from accomplished or won.

I will now return to several more examples which conjoin the microcosmic eye to the macrocosm in the late sixteenth century and early seventeenth. By viewing their symbolic and, perhaps, real connections, we may begin to understand how their fates were aligned in the dual revolutions that overturned previous explanatory models of each, and might partially help explain why both revolutions were roughly historically congruent.

The microcosmic eye like the one found in Tomkis and Crooke uncomplicatedly reflected the majesty and order found in the macrocosm. Pierre La Primaudaye’s The French Academie contains yet another comparison of the microcosm to the macrocosm and the eye’s position within that order. La Primaudaye says,

We have yet another point to bee noted touching their situation, which causeth a certaine proportion and agreement to bee betweene the heavens and the head, and between the eyes of the great and little world, and those of the body and soule. … For this cause, as God hath placed the sunne, moone, and all the rest of the lights above named, and the eyes that are created to receive light from them, and to be that in man who is the little world, which the sunne, moone, and other lights of heaven are in this great universal world. Therefore as much as the eyes are as it were the images of these goodly bodies and celestiall glasses, they occupie the highest place in this body of the world, whereof they are as it were the eyes, to give it light on every side. For this cause also the eyes are more fierie, and have more agreement with the nature of fire, then any other member that belongeth to the corporall senses. … In all these things we see a goodly harmony and agreement betweene the great and the little world, the like whereof wee shall also finde betweene the worlde and the spirituall heaven, whose sunne and light is God, and betweene the eyes of the soule and of the minde. (La Primaudaye 77-78).

In La Primaudaye’s analogy, the eyes represent not the earth but the celestial sphere of the heavens within the microcosm of the body. The eyes receive the light of the world, but also serve as the light of the body. He goes on to suggest that the eyes’ close proximity to the inner senses and especially to reason also confirms their connection to both spiritual as well as bodily light. At the same time, he also notes a distinction between the fleshly or bodily eye and the eyes of the mind and soul by comparing the bodily eye and its received light to the corporeal world and the physical sun to the spiritual heaven whose sun and light is God. La Primaudaye links the corporeal eye to the spiritual or intellectual eye and the corporeal world and light to the divine world and light through a chain of signification and correspondence.

The anagogical significance shines through earlier in La Primaudaye’s discussion of vision when he talks about the special role the bodily, fleshly, or corporeal eye plays in acquiring knowledge and in understanding the divine. He says that the eyes’ “nature approacheth nearer to the nature of the soule and spirit, then any other, by reason of the similitude and agreement that is betweene them,” and proceeds to detail their function in natural and spiritual knowledge and understanding, saying,

…They are given to man chiefly to guide and leade him to the knowledge of God, by the contemplation of his goodly works, which appeare principally in the heavens and in al the order thereof, and whereof we can have no true knowledge & instruction be any other sence but by the eies. For without them who could have noted the divers course and motions of the celestiall bodies? … It is the first Mistresse that provoked men forward to the studie and searching out of science and wisedome. For the sight is ingendered admiration and wondering at things that are seene: and this admiration causeth men afterward to consider more seriously of things … In the end they come to the studie of science and wisedome, which is the knowledge of supernaturall light, namely of the light of the minde, unto which, science and doctrine is as light to the eye, so that it contemplateth and useth by that, as the eye seeth by light. (La Primaudaye 68-69).

The associations and interrelations of the bodily eye and the intellectual eye, and the corporeal light and the light of God were fairly conventional at least since Augustine, and their deployment in both analogical and anagogical systems underscores the conventional parallels and relationships established between them. While distinguished from one another, conventional theories connected the two and helped theorists explain the frisson and connection between the corporeal and spiritual worlds.

Many popular discussions of the superiority of the eye also proclaim that its primary Godly purpose was to acquire knowledge of the world. In this, many stressed the heavens as the best object one’s eyes could focus on to inspire heavenly thoughts and greater contemplations. In his Nosce Teipsum, John Davies, for example, plays with the conventional association with looking to the heavens as leading to knowledge when he describes that

These Mirrors take into their litle space

The formes of Moone and Sunne, and every Starre,

Of every Body, and of every place,

Which with the worlds wide Armes embraced are.

Yet their best object, and their noblest use,

Hereafter in another world will bee,

When God in them shall heavenly light infuse,

That face to face they may their Maker see.

Here are they guides, which do the Body leade;

Which else would stumble in eternall night;

Here in this world they do much knowledge reade,

And are the Casements which admit most light. (Davies 42).

Davies suggests that true knowledge and a true light will not come to the eyes until after death, but he also associates the corporeal light of the world with knowledge suggesting that that corporeal light, as in La Primaudaye, can lead to contemplation of higher things.

Science, including astronomy and anatomy, derives from the wonder generated by the corporeal eye, leading a perceiver from the physical sensation, to contemplation of the natural world, to a contemplation of God’s magnificence. It was the searching eyes of astronomers and anatomists that would soon challenge the conceptions of both the microcosmic eye and the macrocosm.

This returns me to the Augustine notion of three eyes with which I opened this post. While Augustine established three types of eye (the bodily eye, the spiritual eye, and the intellectual eye), all three converge and are mediated by what I call the paramaterial Phantasy in many sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century theories of sensation, perception, and cognition. While La Primaudaye too distinguishes the bodily eye and corporeal light from the spiritual eye and heavenly light, both reflect and resemble one another, interlocking them in a theoretical system and conceptual order that represented them as interrelated and mutually informing. It was the second eye, which, according to Augustine, was the eye of the spirit, but which according to many early modern variations was the eye of the mind, the Phantasy which was often thought to mediate the relationship between the external senses and the intellect and soul.

Not everyone had faith in the powers of the bodily eye and its corporeal light, however. In some theological accounts, the bodily or fleshly eye can lead one into spiritual blindness. The implication lies behind the passage from the La Primaudaye quotation above but the relationship remains one widely repeated in the early modern period. George Hakewill, English Calvinist theologian, argues that the bodily eye can lead to spiritual blindness and sin. Hakewill’s Vanitie of the Eye details many spiritual diseases resulting from the bodily eye, criticizing those who overly commend it, saying,

Though manie and singular bee the commendations of the nature and frame of the eie, & the use of it in the ordinary course of life bee no lesse diverse then excellent as wel for profit as delight, yet the dangerous abuses which arise from it not rightly guided, are so generall, and almost inseparable, that it may justly grow to a disputable question whither wee should more regard the benefit of nature in the one, or the hazard of grace and vertue in the other. (Hakewill 1).

For someone like Hakewill, the bodily eye leads to spiritual corruption in the form of lust, greed, envy, and other sins dependent upon or having their origin in vision. Later, when listing the diseases incident to the eye, he includes, “those which are many times imparted from the distemper of the braine (with which the eie holdes a marvelous correspondence)” (Hakewill 93). Because of the psychophysiological model of the embodied mind, the distempered brain can affect the eye, and the unruly eye can distemper the brain, and both, to some extent, can undermine the soul. It is this conjunction that I attempt to explore in my work on the paramaterial Phantasy.

Even La Primaudaye, who valorizes sight and champions its role in the production of knowledge of the world and of God elsewhere in the same book, cautions against the power of the corporeal eye. While I will expand upon this idea in later posts, the bodily, mental, and spiritual eyes converge in a much more ominous way in a later passage from The French Academie. La Primaudaye cautions people about the types of objects and images their bodily eyes receive. Like Hakewill later, La Primaudaye warns,

let us beware that we feede them not with the sight profane and dishonest things, least they serve to poyson the minde and soule, whereas they ought to become messengers, to declare unto it honest & healthful things. For he that doth otherwise is worthy to have, not onely his bodily eyes put out, & pluckt out of his head but also the eyes of his minde, that so he be may blinde both in body & soule, as it commonly falleth out to many. (La Primaudaye 79).

The three eyes are related through the reference to “poyson,” as the bodily sights are said to “poyson the minde and soule.” While metaphorical, the interrelation of the bodily, mental, and spiritual eyes exceeds metaphor in the way in which many of the references to them explain sensation, perception, and cognition. Just as the corporeal eye could lead to divine contemplation and the illumination of divine light as we saw in my previous example from La Primaudaye, he additionally argues that the bodily eye could also lead to bodily and spiritual corruption.

In addition to the mental and spiritual consequences resulting from a corrupt bodily eye as we have seen in La Primaudaye and Hakewill, still others challenged the type of knowledge the corporeal eye could acquire. The philosophical skeptics, even before Descartes, questioned the knowledge humans could gain through the bodily senses. For them, the eye along with the other bodily senses could not provide certitude or verify judgment. It is my contention that while sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century philosophical skepticism resembles the later seventeenth century developments as one sees with Descartes, those earlier skeptical movements and arguments were expressed through a quasi-Aristotelian and Galenic understanding of the sensitive soul. The developments in optical anatomy might have shifted the epistemological horizons even as they deployed tropes available at least since the time of Sextus Empiricus. Skeptics often challenged the paramaterial nature of the mind and its objects, emphasizing enclosure and the individual in what I call a perimaterial system. (See my previous post on philosophical skepticism here, and my sketch of the paramaterial and perimaterial here).

The eye as microcosm survived the challenge Colombo offered when correcting the situation of the crystalline humor within the eye. This process of de-centering the eye’s long-standing sovereign and seat of the visual power happened over the course of the time period from roughly 1543 to 1619, and although it would take much longer before its full effects were felt, the revolutionary potential of such a change in optical anatomy should be recognized. Later philosophers like René Descartes, Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and George Berkley were still grappling with some of the ramifications of the real image within the eye well into the eighteenth century.

Part of this new approach to physiology was to split the function of the eye from the broader understanding of “vision,” and refusing to speculate beyond the mechanical processes that occurred within the eye. Kepler declared that the mental processing of sensory data was beyond the scope of his argument, and as David C. Lindberg puts it “optics, [Kepler] argues, ceases with the formation of the picture on the retina, and what happens after that is somebody else’s business.” Lindberg suggestively notes,

It is perhaps significant that Kepler employed the term pictura in discussing the inverted retinal image, for this is the first genuine instance in the history of a real optical image within the eye—a picture, having an existence independent of the observer, formed by the focusing of all available rays on the surface. (Lindberg 202).

What Lindberg lauds as the first “real optical image within the eye” also points towards the extinction of another form of “image” within the eye that “had an existence” that was not “independent of the observer,” and, as I will argue, the extinction of images within the mind of that observer that resembled the world it represented. While not, according to Lindberg, a “real optical image within the eye” the previous image within the eye was something more, a product of an eye that depended upon the living eye of an observer that was thought to have more contact with the external world, and, even more importantly, perceived that world with the same orientation as perceived by the mind through images that resembled their objects.

Altering that previous arrangement, not only in the process of de-centering the crystalline humor but also in the Keplerian revolution that made the lens subservient to the retina and its retinal image, might challenge the important system of correspondences established between the eye and the macrocosm. This might partially help explain Vesalius’ misrepresentation of the crystalline humor as well as the continued reiterations of the mediate early modern eye in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. While we have no reason to doubt Colombo’s criticism of Vesalius’ dependence upon the animal eyes for his optical anatomy, and while incredibly speculative on my part, it is possible that the importance assigned to the central placement of the crystalline humor colored Vesalius’ perception of his optical anatomy. The anatomist, coming to the eye with cultural constructions and an a priori understanding of the eye’s function, found his perception of the eye shaped such constructions, not allowing him to see what was before his own eyes.

What is less speculative is that variations of the Galenic eye persisted to a degree well after Vesalius’ mistake was registered and noted and that those depicting the mediate early modern eye often did so through descriptions developed out of the earlier model. One wonders why early modern optical anatomists did not develop a modern representation of the eye until 1619 with the lens positioned just behind the pupil and towards the very front of the eye and without representing the whole of the eye as a perfect sphere. In this, I am more convinced that the a priori system of correspondences which structured the perception of the eye distorted its position because of the stress on the microcosmic structure of the eye as well as upon the centrality of the crystalline humor in the process of vision.

As I discussed in the conclusion of part one of this essay, I believe these popular beliefs and cultural constructions shaped discourses on ocular anatomy, which were, in turn, shaped by them. The system of correspondences and the emphasis on the eye as a microcosm reflected the shape, order, and majesty of the macrocosm. Historically congruous, the de-centering of the microcosmic eye and the de-centering of the Earth within the macrocosm historically emerge together to challenge long-standing authorities and chains of significance. The changes to optical anatomy might not have faced the same type of outrage as the reorganization of the cosmos, but it would profoundly shape and influence subsequent thinkers and their theories of sensation, perception, and cognition.

The system of correspondences, an a priori system of interconnections between world and cosmos, part and whole, slowly decayed under the developing power of a posteriori experimental science. At the same time, those systems of correspondences did not quickly or easily relinquish their hold on the understanding of the world and of the human body even as the new scientific gaze loosened their grip. It was precisely this power of mental Idols which Francis Bacon hoped to eradicate from his New Science because their influence could shape and distort an understanding of the world (see my previous post on Bacon’s Idols here). Even before Bacon, Vesalius attempted to correct the undue influence of classical thought on an understanding of the body, but, for whatever reason, his own work fails in the case of his representation of the eye. Those cultural constructions shaped and informed the development of the New Science even as that New Science attempted to strip knowledge of those very classical and cultural accretions from their perception of reality.

Just as the Copernican revolution would metaphorically turn the world upside down, the Keplerian discovery of the retinal image literally turned the world upside down with respect to the eye. Somewhat displaced from the center of the eye’s orb, the lens, in Kepler’s formulation, played a subservient role to the retinal screen, upon which visible reality was projected. The images within the eye no longer “impressed” themselves on the crystalline humor or bore the same orientation as objects in the external world or as they appeared in the mind of a perceiver, and were, instead, projected upon a curved surface and flipped with respect to vertical and horizontal orientations. Once this explanation eventually replaced the theories which declared the crystalline humor the seat of vision, the image within the eye no longer matched the visual field or the way in which the visual field appeared within the mind. I will return to these ideas more extensively in later posts, but want to say now that this new understanding radically split sensation from perception and, arguably, had ramifications for both the development of mind-body dualism, philosophical skepticism, and formation of the modern self.

While I agree to some extent with David C. Lindberg that Kepler’s theory “at bottom … remained solidly upon a medieval foundation,” I do believe that the retinal image offered a revolutionary change with respect to a person’s theorized orientation with the world despite this medieval foundation. While the full extent of the revolutionary implications would take some time to affect broader cultural shifts, the very fact that Kepler recognized and proposed an image within the eye neither conforms directly to the visual field before it nor to perception as experienced in the mind already took a revolution to see the retinal image as even a possibility. Kepler’s retinal image, of course, finally dethroned the crystalline humor as the seat of vision, but, even before this, anatomists challenged the notion that the crystalline humor occupied the physical center of the eye.[v] In this development, anatomies of the eye moved the crystalline humor from its place of prominence at the center of vision to a de-centered place.

The revolution of the eye involved in unseating the crystalline humor as the centralized power of the human eye, but it also literally de-centered the seat altogether. I cannot help but think this moment of de-centering within the microcosm of the eye itself prefigured and paved the way for radical re-envisioning and restructuring the macrocosm. I also cannot help but think that Kepler’s discovery of the retinal image and the consequent displacing of the crystalline humor combined with the Copernican revolution also helped dismantle the importance of the a priori system of correspondences between microcosm and macrocosm altogether. While I will return in a later post to discuss the emergent tensions between the paramaterial and the perimaterial and the type of philosophical skepticism that was available in the period preceding the real image’s influence upon the sensory system, systems of cognition, and the sense of “selfe,” I must for now, like Kepler, stop at the “opaque wall” of the retinal screen.

Works Cited

Banister, John. The Historie of Man. London 1578. (The English Experience 122). Amsterdam: Da Capo Press, 1969.

Bartisch, George. [Opthalmodouleia] Das ist Augendienst. Dresden: durch Matthes Stockel, 1583.

Clark, Stuart. Vanities of the Eye. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Colombo, Realdus. De re Anatomica libri XV. Paris: Apud Andream Wechelum, sub Pegaso, in vico Bellouaco, 1562.

Crombie, A.C. “The Mechanistic Hypothesis and the Scientific Study of Vision.” Science, Optics, and Music in Medieval and Early Modern Thought. London: The Hambledon Press, 1990. 175-254?

Crooke, Helkiah. Mikrokosmographia. A Description of the Body of Man. [London]: William Iaggard, 1615.

Davies, John. Nosce Teipsum. London: Richard Field for John Standish, 1599.

Descartes, Rene. Selected Philosophical Writings. New York: Cambridge UP, 1988.

Du Laurens, Andreas Richard Surphlet translation. A Discourse of the Preservation of the Sight: Of Melancholike Diseases; of Rheums, and of Old age. London: Felix Kingston for Ralph Jacson, 1599.

Guillemeau, Jacques. A Worthy Treatise of the Eyes contayning the knowlege and cure of one hundred and thirteen dieseases, incident unto them. London, 1587.

Hakewill, George. The Vanitie of the Eie. Oxford: Joseph Barnes, 1608.

Kepler, Johannes. Ad Vitellionem Paralipomena, Quibus Astronomiae Pars Optica Traditur. Francofvrti: Apud Claudium Marnium & Haeredes Ioannis Aubrli, 1604.

Lindberg, David C. Theories of Vision from Al-Kindi to Kepler. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981.

Paré, Ambroise. The workes of that famous chirurgion Ambrose Parey translated out of Latine and compared with. London: Th[omas] Cotes and R[obert] Young, 1634.

Park, David. The Fire Within the Eye. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton UP, 1997.

Platter, Felix. De Corporis Humani Structura et Usu. Libri III. Basil: Per Ambrosium Frob., 1583.

Scheiner, Christopher. Oculus Hoc Est: Fundamentum Opticum. Apud Danielem Agricolam, 1619.

Spruit, Leen. Species Intelligibilis: From Perception to Knowledge. Volume Two: Renaissance Controversies, Later Scholasticism, and the Elimination of the Intelligible Species in Modern Philosophy. New York: Brill, 1995.

Summers, David. Vision, Reflection, & Desire in Western Painting. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Tachau, Katherine H. Vision and Certitude in the Age of Ockham. Optics, Epistemology, and the Foundation of Semantics. Amsterdam: Brill, 1988.

Tomkis, Thomas. Lingua, or the Combat of the Tongue and the Five Senses for Superiority. London: G. Eld for Simon Waterson, 1607.

Vesalius, Andreas. De Humani Corporis Fabrica. Venice: Apud Franciscum Franciscium & Joannem Criegher, 1568.

[i] Misnumbered as page 646 in the 1615 edition.

[ii]It should be noted that there was some controversy regarding the number of membranes of the eye. While Galen, Vesalius, Crooke and others affirm there were seven membranes, others, like Realdus Colombo, John Banister following him, and others affirmed there were only six.

[iii] I argue that in the pre-Keplerian system of vision that I call paramaterial, these species, including the species acquired by the other senses and re-conjoined by the common sense, retain some theoretical connection between them and their external object originals in many popular discussions, but, even aside from my arguments about the paramaterial, the crystalline humor receives or creates simulacra of external objects.

[iv] While this play has received critical attention spearheaded by the ever insightful Patricia Parker and Carla Mazzio, no one, to my knowledge, has yet discussed the importance of Tomkis’ Visus, Common Sense, and Phantastes. I will discuss Tomkis’ representation of Common Sense and Phantastes in a separate post as they pertain to the paramaterial Phantasy.

[v] I should note that I also think the development of linear perspective in the visual arts probably contributed to the discovery of the retinal image. I would like to talk more about this as an influence on its development but have not yet done the reading necessary to make such a claim at this time. Additionally, the ultimate assertion by Descartes and others that the eye works like a camera obscura reveals that it too made an important contribution to the recognition of the retinal image.